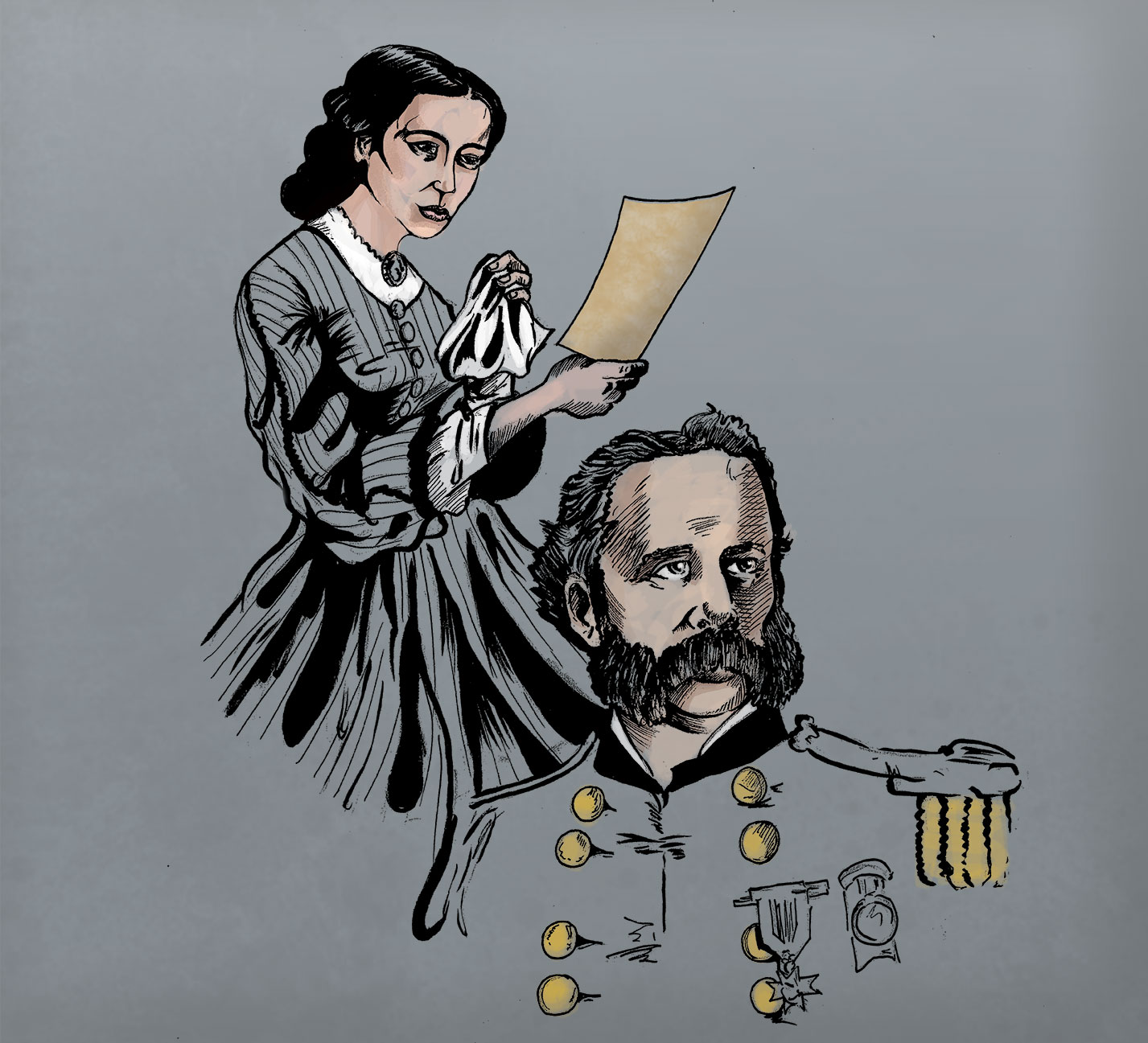

How Lt. Wilmon W. Blackmar risked his life to recapture Confederate-looted love letters written by Libbie Custer to her then future husband George sounds like something out of a movie.

The letters, Blackmar relates in his diary, “had fallen into the hands of a Confederate soldier who read them and found them so beautiful in every way that he would not destroy them but sent them home by a wounded man or some messenger, and the Yankee love letters had become quite famous and were in great demand; they were passed from house to house to be read by the young ladies and were often read aloud for the amusement and edification of young people assembled at sewing circles, parties ... at different houses.”

check out our premium collection

A Confederate prisoner of war tells Blackmar he had seen the letters when he was a guest in a Southern doctor’s home and that he wants to repay Blackmar’s kind treatment of him by taking him there. When Blackmar and the prisoner arrive, Blackmar engages in small talk with the doctor’s two young daughters, eventually working around to the matter of how the girls manage to amuse themselves despite the war. The daughters exclaim that they read Yankee love letters. Blackmar, insisting that Yankees don’t write love letters, eventually cajoles one of them into producing Libbie’s letters as proof.

The Midnight Troubadour

Tough and timeless, this polo is built for the long ride. Featuring a crisp, non-collapsing collar and a rugged, stretchy fabric, it's the perfect shirt for any cowboy's wardrobe.

“She drew out one letter and read it aloud; it was a genuine love letter and a most beautiful one, too. It wound up with, ‘I send you a thousand kisses.’ ‘Did you ever see a kiss in writing?’ said the girl. ‘No, I never did, please let me see how one is put on paper,’ and I rose and stepped in front of her and she handed me the letter. All around the bottom and sides of the sheet were a lot of little rings or ‘O’s’ — the kisses. ‘Well,’ said I, ‘you have defeated me, surely this is a love letter and it bears the marks of being genuine. Did the envelopes bear the postmarks of a Northern town?’ And I gently and quietly reached down and took the packages from her lap to examine them. When I had them, I said, ‘I must acknowledge that I am wrong and you are right. These are Yankee love letters and they belong to my friend and beloved General and I will take them to him,’ and I thrust them into my blouse over my belt.”

When Blackmar reveals the true purpose of his visit, “The frightened girl gave a most unearthly scream and instantly every door on the sides and end of the room except the one from the piazza, from which I entered, was thrown open and one or more Confederate soldiers appeared in each doorway. Like a flash photograph, I took in the situation at a glance. One of them had a terrible wound in or near his eye, it appeared as if his eye was out of its socket and hanging down towards his cheek, a ghastly sight; another carried his arm in a sling. ... As I glanced around I thought they were all wounded. ... [T]hey were Confederate soldiers hidden in this Doctor’s house and being treated by him professionally.”

Seeing he is in a tight spot, Blackmar addresses the men. “ ‘Gentlemen, I have done this lady no harm, nor do I propose to do so. I have strangely enough found some property belonging to my beloved General, valuable only to him, a bundle of love letters written to him by the woman who is now his wife, and I intend to take these letters to him.’ ” Backing toward the piazza door, he and his prisoner-guide exit hurriedly. “Instantly we were in our saddles and away.”

After an all-night ride, they enter their camp. “[D]rawing up before the sentinel on duty in front of General Custer’s headquarters, I asked if the General was stirring yet, and the sentinel answered ‘Yes, he just looked out.’ As I spoke, the door of the little cottage which the general appropriated for his headquarters was thrown open and General Custer appeared in the doorway. I saluted him and taking the bundle of letters from the breast of my blouse and handing them to him, I asked, ‘Do these belong to you General?’ He took them, making no answer, but laughing and dancing ’round the room, I saw him toss the bundle of letters towards the other side of the room, and heard him call out, ‘Oh! Libbie see what he has brought me.’ ... I afterwards heard that Mrs. Custer had come down from Washington and joined her husband that very evening, after I had left camp in quest of the letters, and it was into her lap he tossed the letters I handed him.”

Blackmar’s diary can be found on exhibit through the end of September 2017 at Cisco’s Gallery in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, with the fascinating General Custer Trevilian Collection, which consists in the main of the entire contents of Custer’s personal baggage wagon that was captured by the Confederacy at the Battle of Trevilian Station.

“They took all of his personal possessions, leaving him without even a toothbrush,” says Civil War historian Eric J. Wittenberg, author of Glory Enough for All: Sheridan’s Second Raid and the Battle of Trevilian Station. “They even captured Eliza, his cook. But she made such a royal pain in the ass of herself that the Confederate forces let her escape that night because they didn’t want to deal with her.”

Custer would see Eliza and the love letters again, but not the rest of his belongings. Yet the General had bigger concerns on his mind. The largest, bloodiest all-cavalry engagement of the Civil War, “Trevilians” would come to be known as Custer’s First Last Stand.

“The parallels are striking,” Wittenberg says. “As he did at Little Bighorn, Custer made a reckless charge into the face of enemy forces without looking to see what was in front of him and got himself completely surrounded. In 1876, his luck ran out; in 1864, it didn’t. More important, several of the officers who died at Little Bighorn were with him at Trevilians that day, including George Yates of the 7th Michigan Cavalry.”

In the fighting in central Virginia at Trevilian Station June 11 – 12, 1864, “Custer’s brigade took heavy, heavy losses, such that it was combat-ineffective for several months after,” Wittenberg says. Initially it had looked like it would be a win for the Union. “The first day Union forces captured a Confederate wagon train that ultimately they weren’t able to hold. Custer had seen the wagon train and, without taking precautions, he ordered the 5th Michigan Cavalry to take it, not realizing that a regiment of Confederate cavalry was around.” Blunted first by a force of Georgia cavalrymen, Custer would soon be attacked by his old friend from West Point, Gen. Thomas Rosser and his Laurel Brigade.

“As the fighting swirled around him, Custer was seemingly everywhere,” Wittenberg writes in his article “Custer’s First Last Stand” on the Civil War Trust website. “He rescued a badly wounded trooper of the 5th Michigan while under heavy fire, and was badly bruised by two spent balls that did not break the skin. The officer responsible for the wagons asked Custer if he could take his prize to the rear. The distracted ‘Boy General’ said, ‘Yes, by all means.’ Relieved, the officer left to lead the wagons to safety. As he rode off, one member of the 7th Michigan heard Custer inquire, ‘Where in hell is the rear?’ ”

That’s how bad the melee was.

“It was total confusion,” says David Ingall, co-author of Michigan Civil War Landmarks and former assistant director of the Monroe County Historical Museum in Monroe, Michigan, where Custer (and Ingall) grew up. “Custer had nine lives in the Civil War. It was a miracle he survived the Battle

Source: https://www.cowboysindians.com/2016/04/libbies-love-letters/