It was probably the largest migration of children in human history. From 1854 to 1929, more than 250,000 orphans, runaways, and abandoned children from New York and other cities were sent west and resettled with rural families. At the time, this process was known as “placing out,” but we remember it now as the Orphan Train Movement.

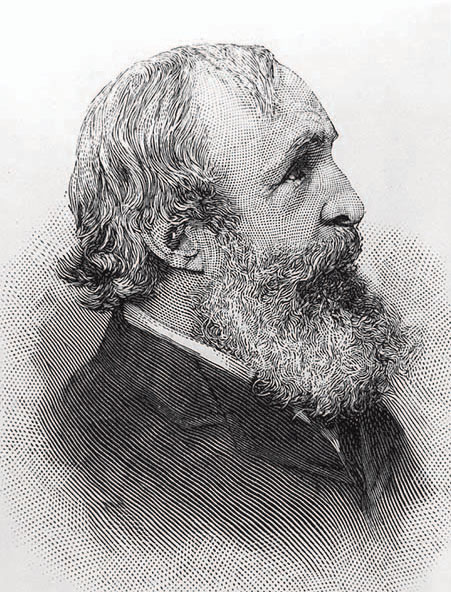

It was the brainchild of an ambitious Connecticut-born minister and social reformer named Charles Loring Brace. Arriving in New York City to study theology in 1848, he was horrified to find thousands of ragged, filthy, half-starved children living on the streets. He couldn’t understand how a benevolent, all-powerful God could allow so many children to live in such misery and degradation, and it shook his faith.

check out our premium collection

Conditions in the city were dire, the gulf between rich and poor wide. While owners of new factories were building mansions on Broadway, working families could barely afford to rent a single windowless room in a squalid tenement building, even with children over the age of 6 working full time. A thousand immigrants a day were arriving in the city, driving down wages and overcrowding the slums even further. Thousands of children were orphaned by disease. Mothers died in childbirth; fathers were often absent either because they had died in factory accidents or were in prison. Destitute parents put their children into grim Dickensian almshouses because they couldn’t afford to feed them. One survey found more than 10,000 homeless children living on the streets, surviving however they could.

The Midnight Troubadour

Tough and timeless, this polo is built for the long ride. Featuring a crisp, non-collapsing collar and a rugged, stretchy fabric, it's the perfect shirt for any cowboy's wardrobe.

Brace was one of the first to see potential goodness in these children and to recognize them as victims of horrible economic and social conditions. Instead of locking up these unfortunates, Brace wanted to expose them to fresh air, hard work, and wholesome Christian families in the rural American heartland. His first step was to found an organization called the Children’s Aid Society, which established the nation’s first lodging house in New York City. Under its aegis, he began an ambitious new program to place vagrant children in distant family homes. The first orphan train went west in the fall of 1854, the last in 1929. Brace died at age 64, in 1890, a little more than halfway through that run, knowing he had done his job and handing over the reins to sons Robert and Charles Jr. to carry on the work.

The legacy of the Orphan Train Movement would be widely felt. From 1890 onward the CAS led the way in the professionalization of child welfare, including training social workers and foster parents. Among the program’s many success stories were orphan train riders who became judges, college professors, bankers, journalists, physicians, farmers, ranchers, clergymen, artists, high school principals, and the wives of men at all levels of society. Two became members of Congress. Some of them and their many descendants would help shape the West.

C&I spoke with Shaley K. George, curator of the National Orphan Train Complex in Corcordia, Kansas, about the movement, its founder, its riders, and its enduring influence on the country and the West.

Cowboys & Indians: Give us the basic overview of the Orphan Train Movement.

Shaley K. George: The Orphan Train Movement ran from 1854 to 1929 and sent an estimated 250,000 children from East Coast cities across the 48 contiguous United States and five continents. Some of the children were truly orphaned; others were half-orphaned, abandoned, and homeless. The first company of 46 children was sent to Dowagiac, Michigan, and arrived October 1, 1854. It took them two boats and two trains to reach their destination. The last known train arrived on May 31, 1929, in Sulphur Springs, Texas, with three children aboard. An estimated 75 to 80 percent of the children found good homes; an even higher percentage went on to be successful individuals, spouses, parents, and friends. They were resilient and chose to succeed.

C&I: In what way is the Orphan Train Movement a Western story?

George: The Orphan Train Movement’s role in westward expansion is not discussed, but the fact is that the children who were being sent from the streets and orphanages of the East to Western homes would go on to help develop the nation as we know it today. They are similar to the settlers who came before them. They came from the East, they lived lives they could not have planned for, and they largely succeeded, helping to develop untamed lands and settle the frontier.

The railroads, of course, play an enormous role in the Western story, and their role in the Orphan Train Movement is no different. A common misconception is that children were only sent to farming communities to become laborers. This is not true. The Children’s Aid Society of New York sent the largest number of children to the Midwest. By 1890, the largest concentration of rail lines in the U.S. was in exactly the same Midwestern states where the CAS sent the most children. These towns had schools, churches, and a community to teach needy children what love and family were about.

The conception of the West was ever-evolving in the minds of Americans during the 1800s. With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the country doubled in size, and the 1840s brought the West Coast and Southwest onto the country’s horizon. By the 1850s, the largest migration of pioneers using the trails was complete and the railroads were moving in. Charles Loring Brace knew that with the technology of the railroads he could place out more children. Without the trains, the placing-out program would not have been as widespread and overall as successful.

Throughout [the] Children’s Aid Society’s annual reports, the phrase “sent west” is traditionally used to signify a company of children being placed outside New York City to the Midwest and farther west. The United States was a growing nation with land that was “unsettled.” When we think of the Wild West today, Dodge City, Kansas, and Deadwood, South Dakota, top the list — both are in Midwestern states. The CAS began placing out its children in surrounding states and the Midwest, spreading its efforts farther out every year. The first Western state to receive children was Colorado in 1872.

C&I: What was the Rev. Charles Loring Brace’s idea of the West that he was sending these orphans to?

George: Father of the orphan trains, Brace, in my opinion, had an idealistic view of the West, as many in the East did. He saw Western families offering the forgotten children of New York City a life full of education, faith, and success. In Brace’s book The Dangerous Classes of New York, & Twenty Years’ Work Among Them, published in 1872, he states, “In every American community, especially in a Western one, there are many spare places at the table of life. There is no harassing ‘struggle for existence.’ They have enough for themselves and the stranger too. Not, perhaps, thinking of it before, yet, the orphan being placed in their presence without friends or home, they gladly welcome and train him.”

C&I: What programs were put in place to support this altruistic idea that led to such a massive migration?

George: What we now refer to as orphan trains were actually called placing-out programs and mercy trains during the Orphan Train Movement, depending on which sending organization was placing the child. There were roughly 30 organizations that placed children, with three main organizations — the Children’s Aid Society, the New York Foundling Hospital, and the New York Juvenile Asylum — doing the majority of the placing.

The C

Source: https://www.cowboysindians.com/2017/05/riding-the-orphan-train/