When I was growing up in a little Iowa town, every kid I knew wanted to be Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, or some other silver screen hero, leaping off galloping stallions onto teams of crazed horses to stop runaway wagons and save pretty damsels.

On January 15, 2009, Capt. Chesley Burnett Sullenberger III, who grew up in a little Texas town and had his own cowboy heroes, totally trumped our runaway-wagon fantasies when he miraculously landed a badly damaged US Airways Airbus 320 onto the freezing waters of New York’s Hudson River. He saved the lives of all 150 passengers and five crew members. Like a good old-fashioned western, it captivated the country with the drama of the rescue and the skill and grit of the protagonist pilot.

check out our premium collection

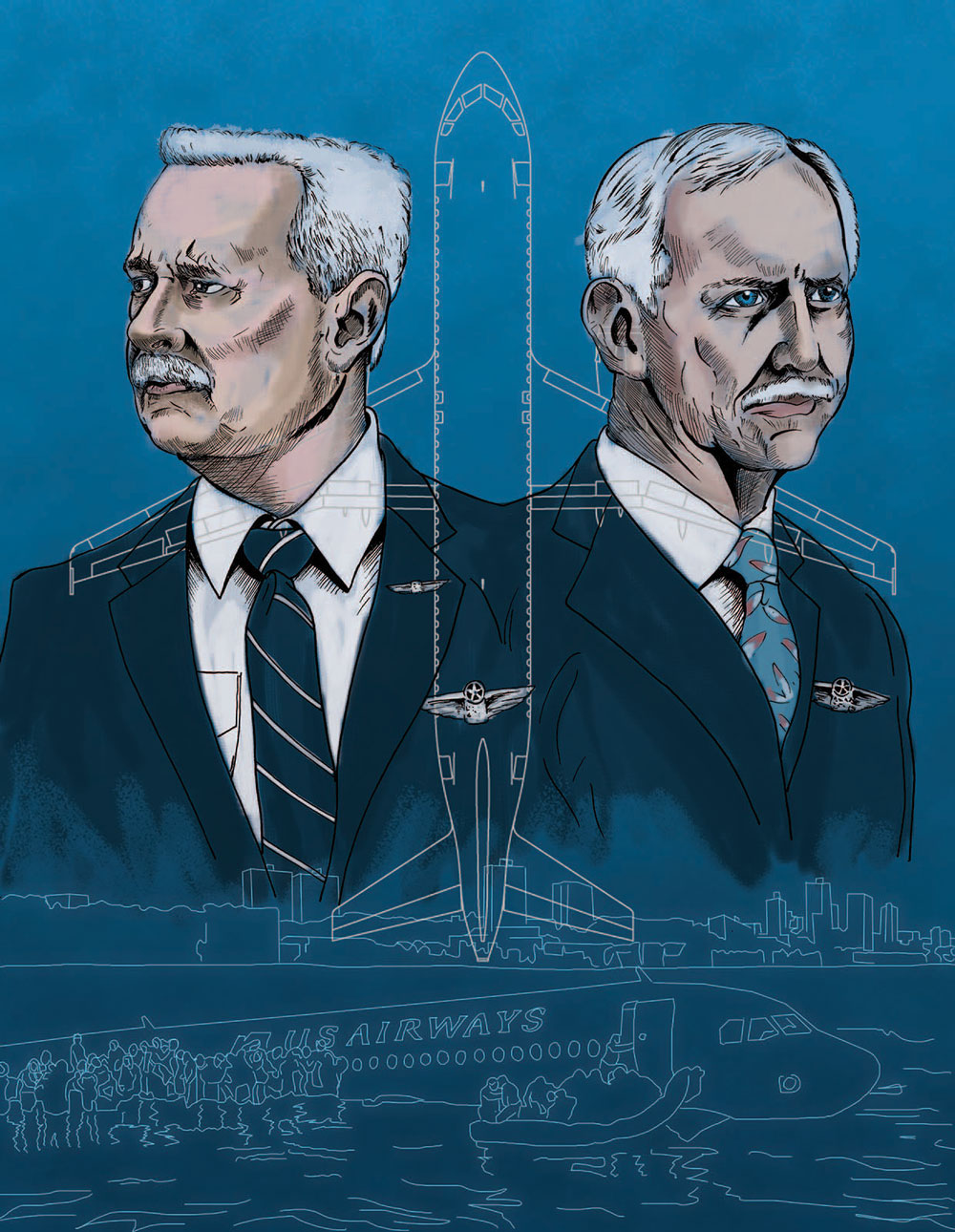

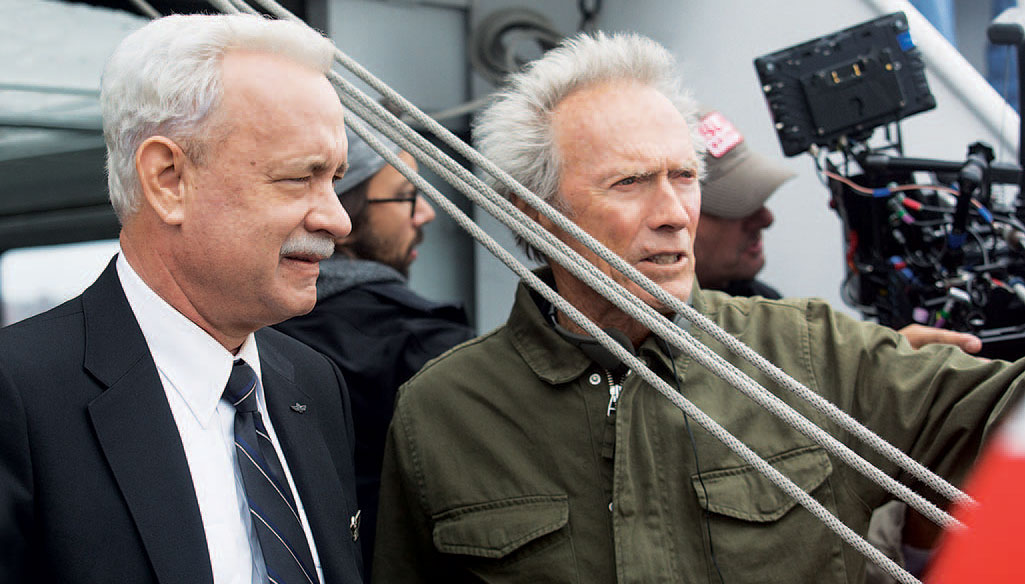

The feat was hailed as “The Miracle on the Hudson,” and the pilot known as Sully became an instant American icon. Now, fellow icon Clint Eastwood has made a movie about the man and the miracle. Sully, starring Tom Hanks, is due in theaters on September 9.

The son of a World War II veteran, Sullenberger grew up 10 miles outside of Denison, Texas, a rural town 75 miles north of Dallas. “I had a lot of movie and TV heroes when I was a boy,” he recalls, “actors like Jimmy Stewart and Gary Cooper and several TV heroes like the Lone Ranger; Sky King, who chased bad guys in his Cessna 310; and Rowdy Yates from Rawhide [Clint Eastwood’s career breakthrough role].”

The third-generation Sullenberger from Denison, he grew up steeped in western movie and TV heroes, Texas values, and Lone Star traditions. “As a kid, I wore the cowboy boots and the cowboy hat, and we kept an 1873 Winchester repeating rifle and a nickel-plated Colt single-action revolver in the house.”

The Midnight Troubadour

Tough and timeless, this polo is built for the long ride. Featuring a crisp, non-collapsing collar and a rugged, stretchy fabric, it's the perfect shirt for any cowboy's wardrobe.

More than the trappings and regalia, Sullenberger believes his rural Texas upbringing helped him develop character and integrity. “The size of the community and the post-war Eisenhower era made it a very safe, stable environment that promoted a real sense of community,” he says. “We talked to and interacted with our neighbors, which people don’t do so much today. We were raised to be self-sufficient, yet to also count on each other and be held accountable by the community to do our part.”

From the time Sullenberger was out of short pants, he never wanted to be anything but a pilot. He learned to fly as a teenager from instructor L.T. Cook Jr. in a single-engine, tail-wheeled two-seater. “His teaching was the foundation for everything I learned about flying and safety thereafter. He drummed it into me that the aircraft had to be an extension of myself — and that I must always have a situational awareness of where the aircraft is, the altitude, the airspeed.

“He emphasized that I must be in control of and never at the mercy of an airplane. Those lessons were vividly present with me in that cockpit on Flight 1549.”

After graduating as an Outstanding Cadet from the Air Force Academy and flying F4-Phantom fighter jets for his country, Sully went to work for Pacific Southwest Airlines in 1980, which was merged into US Air in 1988, later to become US Airways. He flew pretty much without incident until that fateful day in 2009, when, with 26 years of captain’s experience under his belt, he took off from New York’s LaGuardia Airport bound for Charlotte, North Carolina.

Almost immediately, his plane struck a large flock of Canada geese, whose feathers lodged in and disabled both engines, causing one to catch fire. He was at the controls of a 151,000-pound airplane that had exactly zero thrust. A passenger described the sound in the engines like that of tennis shoes knocking around in a clothes dryer.

Sullenberger would later say in a 60 Minutes interview, “It was the worst, sickening, pit-of-your-stomach, falling-through-the-floor feeling I’ve ever felt in my life.”

This is where the years of training and the thousands of hours of flying — and Sully’s inherently calm demeanor — took center stage. The duration of the flight was a mere five minutes, only three and a half minutes from the time he struck the birds. He had to make exactly the right decision and make it fast.

He says the discipline he had developed since he was a boy and the crisis-management skills he learned along the way were key factors that pulled him through that day. “You have to have team skills, develop great communication, and have a plan you can put into place in any crisis.

“If you’ve already done your homework and built your team that way, you don’t have to reinvent the wheel; you just have to put the last few spokes in place, which is what we did on the Hudson that day.”

Sully had never trained to land on water — nor has any pilot, because no such simulators exist. “Yet we had trained so well to have a shared responsibility for the outcome that my co-pilot, Jeffrey Skiles, and I were able to communicate wordlessly. He saw what was happening, he heard me on the radio, and he knew exactly what his part would be in this landing.”

They were past the point of no return to LaGuardia and too far from New Jersey’s Teterboro Airport to land safely without a great risk of killing the passengers and people on the ground. So it was the cold, dark waters of the Hudson or nothing. “You know, from the outset of that accident till we landed, I never thought I was going to die that day,” Sullenberger says. “I just wasn’t sure at first how I was going to pull that off.”

Most forced water landings end catastrophically, but Sully and Skiles had no choices left, and they ditched into the Hudson River unpowered, not unlike a gigantic glider — barely missing the George Washington Bridge because of Sullenberger’s skillful maneuvering. He also knew that if he didn’t come in at exactly the proper angle, or if he let the plane stall, it would hit the water in a way that would break it into pieces and likely kill everyone.

It was an absolutely perfect landing. But the miracle was only half over. Sully and his crew quickly evacuated passengers onto the wings as water seeped into the cabin from a leak in the tail. “I thought about what my father had always said about being responsible for others, and that’s why I went back into the cabin twice to get a head count,” Sully reflects. “I had never trained to do two walk-throughs, but I couldn’t exhale until I knew everyone was safely out of that plane.”

While no one knew it, within 26 minutes, that plane would fully submerge.

Rescue crews in ferry boats and helicopters came swiftly and in the nick of time. With the plane sinking and the water temperature barely above freezing, all passengers were rescued. Sullenberger was the last one off before t