Neil Holmes looked like he might be dead.

The professional bull rider was facedown and motionless in the dirt after his ride atop a bull named Rodeo Time came to a swift and violent end. At about the five-second mark during Holmes’ ride in Round 3 of the 2016 Professional Bull Riders World Finals at the T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas, Rodeo Time threw his head backward at the exact instant Holmes lunged forward. The back of Rodeo Time’s head smashed into Holmes’ forehead, and it appeared that Holmes lost control of the ride, if not consciousness.

check out our premium collection

Holmes’ body snapped backward, then lunged forward and collided headfirst with Rodeo Time’s head a second time. The rider jelly-slid sideways and downward as Rodeo Time thrashed angrily. “Oh, no,” the PA announcer yelled.

The Midnight Troubadour

Tough and timeless, this polo is built for the long ride. Featuring a crisp, non-collapsing collar and a rugged, stretchy fabric, it's the perfect shirt for any cowboy's wardrobe.

Holmes did nothing to break his fall, instead crashing to the ground like a rag doll flung by an angry child. Tandy Freeman rushed to his side. Holmes didn’t move for several seconds. Rodeo fans know that if Freeman enters the arena, it’s potentially serious. For more than two decades, he has served as PBR’s medical director and fills a similar role for Wrangler National Finals Rodeo’s Justin Boots Sportsmedicine team.

Finally, Holmes’ legs moved, though it’s not entirely clear whether he did that on his own or if it was the doctors rolling him over.

Freeman took Holmes to his makeshift doctor’s office adjacent to the bull riders’ locker room for treatment. When Holmes staggered out more than an hour later, he still looked and sounded dazed. Blood covered his hairline, streaked across his forehead, and stained his clothes. “I can’t remember s---,” he said.

The most remarkable thing about this scene is that it wasn’t remarkable at all. There are any number of equally brutal crashes in most, if not all, PBR and NFR competitions — and it’s up to Freeman to patch up these cowboys and get them ready to ride again.

Or to ground them if they are too injured to go on.

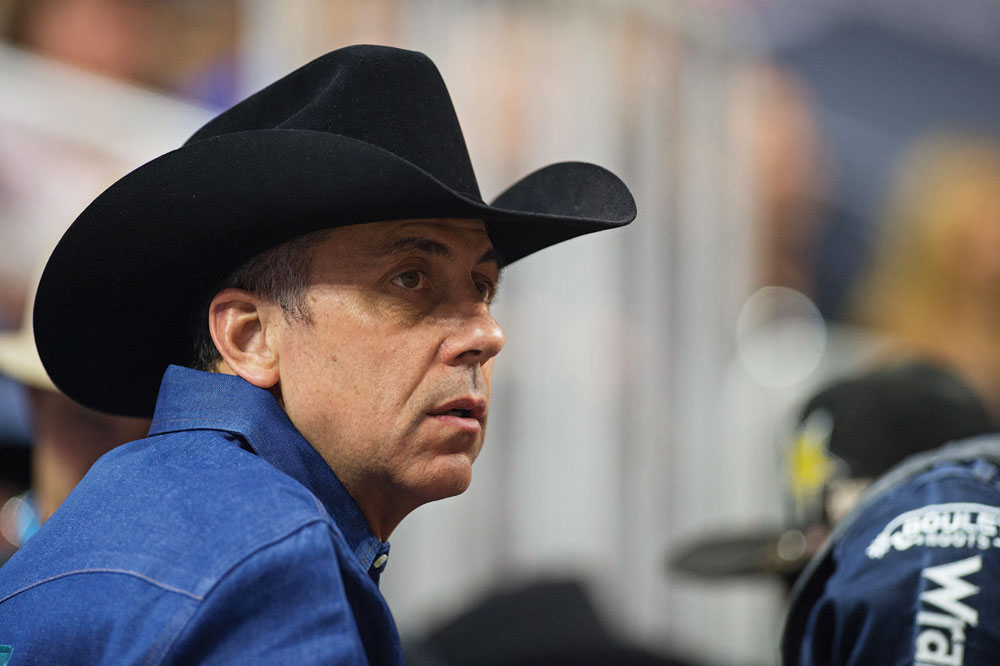

Tall and broad-shouldered, Freeman is bigger in stature than nearly all of the cowboys he treats. He wears a crisp PBR dress shirt, slick boots, and a cowboy hat that sits tilted back a degree or two. His big smile is a tick lopsided. The dark hair at his temples is graying. He believes in eye contact and telling the truth, even when it’s a hard truth, in blunt terms.

He has the air of a man who has seen it all, and, at least in the rodeo world, he has. He’s missed only a handful of events in more than two decades of working with PBR, and he estimates he has seen 100,000 bull rides and the thousands of bloodied, bruised, and broken cowboys that have been the result.

Freeman grew up in Texas but wasn’t a frequent rodeo attendee. As an orthopedic surgery resident, he had a six-week rotation with Dr. J. Pat Evans, who worked as the team doctor for the Dallas Cowboys and the Dallas Mavericks and also treated rodeo athletes. As Evans planned for his retirement, he enlisted Freeman to take over for him.

Around that time, 20 bull riders banded together to form the PBR. They wanted the best doctors possible — including Evans and Freeman. For a year or so, Freeman simply observed how Evans treated cowboys at rodeo events.

Training alongside Evans proved invaluable. Evans was immensely popular among the cowboys, and riders were wary of a new doctor. The fact that Freeman came with Evans’ endorsement went a long way toward winning the riders’ trust. His skill as a doctor solidified it.

“I remember the first time J. Pat brought him around,” says Ty Murray, a nine-time world champion and cofounder of PBR. “You’re always a little skeptical. ‘Who’s this new guy?’ It’s pretty weird looking at it from this side now. We feel pretty darn lucky to have him. It’s important when you’re talking about a sport like this that you have a doctor that you really believe in.”

Riders believe in Freeman because he knows his patients and what they’ve been through to get to the professional level in the sport. For the uninitiated, watching a rider get stomped or head-butted by a bull can be harrowing. But Freeman had plenty of trauma experience before starting the job. He had trained as a surgery resident in Utah for three years, operating on patients who, as he puts it, “ski into trees and run cars off cliffs.” He also trained as an orthopedic surgery resident at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas, which has one of the busiest trauma centers in the country. All of this prepared him for scenes in the bull-riding world that might have stunned less-experienced doctors.

Now, 25 years later, little, if anything, surprises him. Most nights he watches closely from the side of the chutes. He enters the bull ring only when he has to. He has seen so many men get stomped on by bulls throughout the years that he knows in an instant which incidents are serious.

A case in point occurred the same night Holmes was hurt. A bull threw Zane Cook to the ground and stepped on his head. The crowd gasped. It looked like the bull had bashed Cook’s brains in. Freeman knew better. He did not move from his spot at the chute. The blow from the bull’s hoof had been glancing, not direct, a detail Freeman — but few others — noticed instantly. Cook got up, dusted himself off, and walked away, proving Freeman’s instant diagnosis correct. “It was a flesh wound, so to speak,” Freeman says.

What his eyes don’t tell him, his hands can. Murray says Freeman “can grab the bottom part of your leg and know what ligament you tore without looking at the X-ray.”

It’s work like that — combining knowledge of competitors and expert diagnosis — that led PBR to honor Freeman with the 2016 Jim Shoulders Lifetime Achievement Award, bestowed annually on a non-rider, for his contributions to the sport. He also received the Texas Rodeo Cowboy Hall of Fame Western Heritage Award in 2008 and was named the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association Texas Circuit Man of the Year in 2004 and the Resistol Rodeo Man of the Year in 2010. He was inducted into the Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame in 2013.

Until a few years ago, Freeman could advise PBR competitors to sit out, but he could not order them to do so. That changed as leaders in the sport decided that the athletes needed to be protected from themselves.

That has added a layer of complexity to Freeman’s decision-making, and it’s a responsibility he takes seriously. Bull riders only get paid if they last eight seconds. If Freeman won’t let them ride, he is denying them the opportunity to make a living.

“He tries to help us in every way he can,” says J.B. Mauney, the two-time world champion and face of PBR. That is not to say Mauney always agrees with Freeman. “There’s been quite a few times me

Source: https://www.cowboysindians.com/2017/11/the-doctor-in-the-dirt/